Making Baby Q

Sept 2017: Parenthood Ahead!

Bright-eyed and brainstorming baby names, we attend our first fertility appointment under several flawed assumptions:

• Getting pregnant will be easy.

• Insurance will cover it.

• Treatment will be physically painful, not emotionally painful.

We understand about 25% of what the doctor says, and 10% of what the financial counselor says. We sign the papers anyway, and leave with a list of follow-up tasks both medically and logistically perplexing.

For the next two years, we say we’ll start on them "over the weekend."

Jul 2019: First Steps

Nadine gets baseline testing. She and our donor get genetic testing. A genetic counselor outlines the risks of blending their carrier conditions; fortunately, they're compatible.

Nadine gets an excruciating HSG (hysterosalpingogram) to ensure her fallopian tubes aren’t blocked. She nearly passes out—this photo was taken BEFORE the test.

Sept–Dec 2019

Our donor gets a medical workup and makes his donation. The FDA recommends quarantining it for 6 months and then having our donor repeat the tests. (Carefully chosen donors apparently pose greater health risks than do random guys at bars.) We get the sperm waiver notarized at our local tax-filing joint, reducing our quarantine to the minimum of 3 months.

Jan 2020: First IUI (Intrauterine Insemination)

We’re having a baby! (Why wouldn't it work? Nadine took the pills, ate the kale, skipped the coffee, had normal labs and ultrasounds, got the Ovidrel shot at the exact right time.)

We hemorrhage hours meant for sleep, giddy with hopes for our baby. Each night of the two-week wait, we cross a page off our countdown till it’s time for the pregnancy test.

Two weeks later, no second pink line appears. The feelings crash together in a tight, dissonant knot: cheated, angry, sad, confused.

Feb 2020: Second IUI

Denying that well-meaning people could fail twice, we make another two-week countdown. Emily draws faces on the photo of Nadine’s new follicles: our future twins.

The Oxford (lack of) Freedom plan denies coverage for our first IUI and for all future ones. They require 6 months of prior "exposure to sperm," and don't permit the use of medications that increase chances of fertilization. Nadine battles Oxford in appeals, arguing that (1) this policy excludes females in same-sex couples, and (2) at her age, unmedicated IUIs have an abysmal success rate. The fine print of Oxford's form rejection letters reveals that sexual orientation is not among the classes protected from healthcare discrimination in NY State.

March 2020: Third IUI cancelled. Clinic closed.

COVID-19 hits NY. We retreat into hibernation: Nadine's eggs must escape this thing unscathed. When the world reopens in a few weeks, we'll try again.

Jun 2020: Third IUI

Turns out it wasn't just a few weeks, and time is precious when it comes to 39-year-old eggs. Neither of us wants to make a countdown this round.

Banned from insemination day, Emily waits on a bench outside the former FAO Schwarz—flanked by one security guard monitoring a cluster of pigeons. The city is deserted; we stand smack in the middle of Madison Avenue and take selfies. Once home, we try to pass the day like monks on a silent retreat: mindful, humble.

Jul 2020: Fourth IUI

This round we ask to do 2 inseminations on consecutive days. The doctor feels this is a waste of costly sperm, but we resolve that if the problem has been one of timing, we’ll show it who's boss.

Lying in a Lyft post-insemination, the flaking Queensboro Bridge looks majestic. But majesty can easily bleed into hope, and what if hope is just a step away from hubris? We try to unhear the echoes of our doctor's voice: “These follicles look great!” and “You've got ‘textbook [uterine] lining’ again.” If we blot out hope, later despair might be more bearable.

Early Aug 2020: Fifth IUI

Nadine has 3 mature follicles, plus 1 that's well on its way. The doctor asks if we’d like to cancel the cycle: it could yield a dangerous number of multiples, especially if any embryos divide. We opt to proceed anyway.

Standing on the clinic sidewalk with the husbands, Emily eats a Starbucks blueberry muffin while Nadine (maybe) has new life take hold in her.

Two weeks later: there is no new life.

Mid-Aug 2020

Three vials of sperm remain; each insemination requires one to two vials. We can't afford the cost or wait time of getting more. We'd sworn IVF was out of our price range, but that was before push came to shove.

Emily researches clinics with lower IVF pricing. Our current clinic slaps up red tape when told we’re withdrawing our vials. Finally, Nadine lugs the tank a few blocks while Emily waits in the 398th Avis rental of our fertility journey. We wedge the tank in the trunk and drive to Brooklyn, wincing at every pothole and speed bump.

Late Aug 2020: IVF

(In Vitro Fertilization)

At the new clinic, Nadine has an SHG (sonohysterography) to 'map' her uterus. The nurse makes several false starts and calls the doctor in to complete it. Despite the pain, Nadine cracks jokes on the table and can't seem to stop. This should serve as her warning that IVF will erode her mental health and replace it with a dystopian funhouse, but stubborn sparks of hope cloud that message.

Sept 2020: Stimulation Phase

Needles-needles-needles! Pills and more pills! Pre-dawn clinic appointments followed by 7:15am arrivals at Nadine’s 9am job!

Emily is de facto home nurse—YouTube Med School, Class of 2020. She administers 2-3 shots per day; Nadine overcomes her fear of needles. They've read enough to know that these stomach shots are child's play: the progesterone ones in the hips are yet to come.

Sept 28: Egg Retrieval

Our doctor retrieves 15 eggs, 10 of which are mature. (This isn't bad news, but groggy from anesthesia, Nadine sobs hysterically over it. Unsure of how to soothe her, the young orderly breaches COVID policy and ushers Emily in.)

All 10 mature eggs fertilize with ICSI, whereby a single sperm is injected into each one. Next step: we wait.

Sept 28–Oct 5: Attrition

We’ve lurked on Reddit enough to know that the next 6-7 days are all about embryo attrition—online fertility boards refer to this phase as 'IVF Hunger Games.' We jump when the phone rings with the clinic’s daily updates of who's survived another day.

Six of our ten last till day seven. Jolted but optimistic, we send the six cell samples to a Florida lab for testing that will improve our chances of a pregnancy. Three embryos test abnormal, two normal, and one low mosaic (25% abnormal).

In short: two tries left to make a family. Without fertility coverage, we can’t afford another egg retrieval.

Oct 2020: Embryo Transfer Mock Cycle

People transferring embryos need 4-6 days of progesterone shots to foster an ideal uterine environment. This number varies by individual; since we have no margin for error, we do an ERA (endometrial receptivity analysis) to pinpoint Nadine’s specific needs. After 5 days of shots, her uterine lining is sampled and, once biopsied, will reveal how many days of progesterone she needs when transferring an embryo. Some unsuspecting FedEx employee brings the lining to a lab.

IVF Paused

A routine mammogram finds a lump in Nadine’s breast. Some sources suggest that fertility meds can cause this. Nadine gets more imaging, then a biopsy; surgery is recommended.

Nov 2020: Surgery #1

Nadine has the lump “removed.” The resulting pathology doesn’t match that of the biopsy. We excavate the remote but plausible nightmare that Nadine's tissue was mixed up with someone else's. We go elsewhere for a 2nd opinion—Emily's still not allowed in—and learn that the surgeon removed healthy tissue, not the lump. Its full pathology remains unknown.

Dec 2020: Surgery #2

Nadine actually gets the lump removed. We learn more about lawsuits than we ever planned to: namely, that we lack grounds for one. Stress and anger consume us, but we're fortunate to learn that the lump is benign.

Jan 2021:

Prep for First Embryo Transfer

Nadine resumes IVF despite what some say are the breast cancer risks of the meds. Emily summons her YouTube training and assembles a station on the bedroom dresser: alcohol wipes, gauze, band-aids, heating pad, ice pack, various gauges of needles stowed in a box so Nadine doesn't see how long and thick they are.

Feb 26: First Embryo Transfer

The Avis clerk now recognizes us, which is mildly charming and possibly evidence of our declining odds.

Our embryo has survived the thaw and will be carefully deposited into Nadine. COVID protocol restricts Emily to the waiting room during what we're convinced are our child's first moments.

Nadine is sore from progesterone shots in her hips, bloated and queasy from other meds, and burnt out from pre-sunrise ultrasounds. This all melts away as our embryo creeps down the catheter and across the screen like a slowly shooting star. The embryologist hands Nadine its magnified photo, which she and Emily place on the fridge.

March 8

We aren't pregnant, and there aren't words.

Apr 2021

One embryo remains. This feels like some inhumane gameshow: win the grand prize of $1,000,000...or else pay it to the clinic and depart with nothing.

We haven't left NYC in over a year. We try to escape our decaying minds with a trip upstate, where we binge-watch Grey’s Anatomy on a cell phone in our hostel room because (1) we can’t feel our hands outdoors, (2) we can't get COVID before our next transfer, and (3) someone forgot the iPad.

May 2021

Anxiety sky-high, Nadine starts twice-weekly acupuncture on our doctor's advice. Is it working? Who knows. If nothing else, occasionally her heart stops pounding long enough for her to skim the edges of something reminiscent of peace.

We ask our doctor for the 'kitchen sink' meds: anything that might help our chances, even if experimental. We start a 6-week protocol of extra shots and pills.

Jun 3: Second Embryo Transfer

Emily's allowed into the first appointment in over a year!

We hang a onesie on the shelf by the exam table. Either it'll bring good luck, or before long the sight of it will make us ill.

Our embryo survives thaw and creeps across the screen. No souvenir photo this time: the lab camera's broken. We strive not to let this mean anything.

We wait, and for the next eight days, we tell ourselves there's nothing more we could've done. We feed ourselves other canned mantras we only half-believe. We continue shots in the hips to sustain a life that may or may not have already disintegrated.

Jun 11: The Day

5:45am: We head to the clinic to meet our fate via blood test. A nurse will call with results around 2pm.

Heading home, Nadine spots a heads-up penny in the street and picks it up. A half-block later, a pregnant woman inexplicably stands in profile.

The phone finally rings; we hesitate to pick up. When we do, it's not just a nurse...but ALL the nurses whom we've come to know.

"Are you SURE?" Nadine prods repeatedly. Tears stain our t-shirts, but this time they're happy tears.

Jun 22: 5 Weeks, 3 Days

For the first time, we visit Avis without resentment.

We see the yolk sac (interim placenta) and fetal pole: collectively a faint, wormlike circle. We learn that our guy has attached in a good spot.

After so much failure, joy feels strange and suspicious—more like relief than celebration.

Jul 7: 7 Weeks, 4 Days

We hear the heartbeat: 144 beats per minute.

While this is a milestone, the pregnancy is still fragile. We plead with our guy every day to hang on.

Our fertility clinic says it's time to graduate, but we don't want to leave the doctor who got us this far. We all break COVID protocol to exchange hugs, then count down the days till our first OB visit.

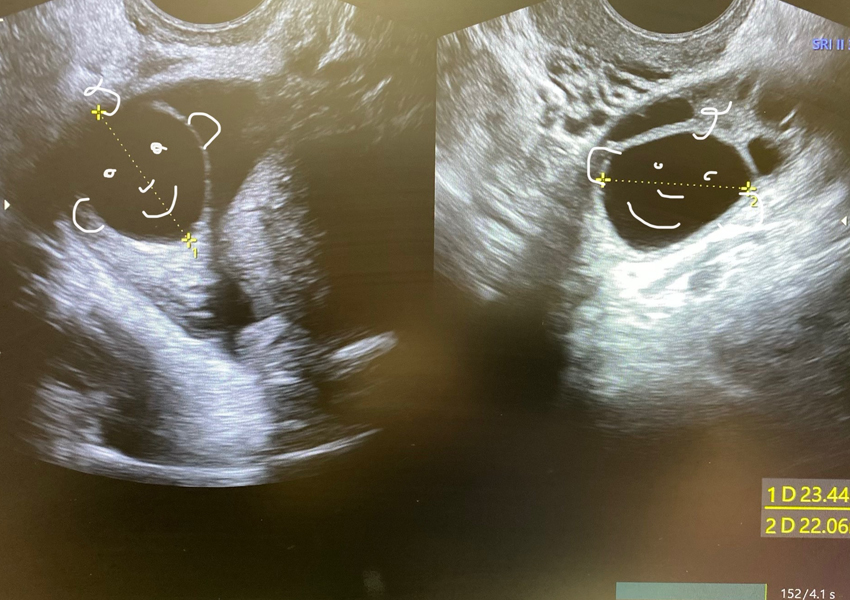

Jul 20: 9 Weeks, 3 Days

At our first OB scan, we're floored that the nondescript creature from two weeks ago has morphed into something more like a teddy bear.

His heart beats visibly in his chest.

He waves his foot [upper left in photo] back and forth, showing off visible toes.

Aug 5: 10 Weeks, 6 Days

This concludes twelve weeks of daily progesterone shots. As painful as they've been, stopping them feels irresponsible.

Nadine's tissue damage slowly heals over the coming months; her back and thighs hurt less and less. We know that the hardest part is behind us—regardless of what pregnancy brings.

Fertility treatment stole our sleep, isolated us, made us angry and jealous, distracted us from work, depressed us...and yet ultimately strengthened our marriage.

Aug 13: 12 Weeks, 6 Days

(Nuchal Scan)

We opt for a nuchal translucency scan, which measures the skin fold at the back of the baby's neck. This checks for risk of birth defects such as Down's Syndrome, Trisomy 13 and 18, heart problems and other chromosomal abnormalities.

Our little guy is not concerned, and puts on quite a show—kicking, flipping and sloshing around. Another hurdle crossed: the doctor reports that everything looks normal.

Oct 12: 21 Weeks, 3 Days

(Anatomy scan)

Our little guy weighs an estimated 1 lb 1 oz, placing him in the 58th percentile for weight. He gets his heart rate checked, his lungs inspected, and has measurements taken of his brain, spine, kidneys, bladder, arms, legs, toes, fingers and more.

Nov 18: 26 Weeks, 5 Days

(Growth Scan)

Our guy now clocks in at 2 lbs 7 oz; he's pulled ahead to the 73rd percentile for weight. All of his measurements are blessedly normal.

Mid-scan, the technician switches from a standard ultrasound to a 3-D one. It's a shock to see flesh instead of bone, and to glimpse even the primitive terrain of eye sockets, nostrils and a little pout. We're smitten.

Dec 22: 31 Weeks, 4 Days

(Growth Scan)

Having heard that this site will soon launch, our guy shies away from his latest photo shoot. He hides behind the placenta, holding his hands and the umbilical cord in front of his face.

He weighs an estimated 4 lbs 13 oz, placing him in the 81st percentile. Our estimated due date is now 2/9, originally 2/19. His arrival feels more imminent with each passing day, and his movements are now forceful enough to be seen from the outside.

Since June 11, our child has reassured us by way of 21 heads-up pennies, nickels and quarters found on NYC streets. We’ll frame them all one day. When he’s old enough, we’ll thank him—for telling us he's OK long before he could speak, for holding on through these tenuous months.

Before he was with us—when he sat frozen in a lab and part of him flew unchaperoned to Florida—we learned what it meant to believe in him. Later, waiting to learn whether he'd clung to a life source or dropped into oblivion, we strove to believe—and he saw fit to morph our pain into joy.

Shooting-star embryo, active fetus, soon-to-be son, you’ve cleared every hurdle that science has set for you. You were strong before you had any will. We’re eternally grateful.